In January of 2020, I went on my last run. I was chronically injured and knew I should have stopped years earlier, but running wasn’t just exercise—it was a pillar of my life. For thirty years, it grounded my routine, steadied my mental health, shaped my career, and gave me a sense of ease and confidence I only ever found on the road.

My mind wanted to keep running, but my body couldn’t. It’s a familiar story for so many runners, yet one we often carry in silence. How do you step away from something that has been your anchor, your outlet, your daily companion?

It’s time to give that transition the space it deserves. Welcome to The 27th Mile: How to Smooth the Rough Transition Out of Your Running Years.

In this book, I reckon with my decision to quit, my grief of leaving behind a beloved sport, and my rediscovery of purpose, connection, and endorphins on the other side of goodbye.

But this isn’t just my story. I talked to more than fifty amazing, honest, generous women about their running: the highs and lows, the beginnings and the endings.

Some of us are making peace with dramatically less mileage than we used to. Some of us are freshly mourning the loss. And some of us, like me, haven’t run in years. Their stories are woven throughout the book so that no matter where you are on the losing-running spectrum, you’ll see yourself reflected—and feel validated by the experiences of women who understand.

If this sounds like your story—or the story of someone you love—I invite you to join me at The 27th Mile and preorder now. —Dimity McDowell

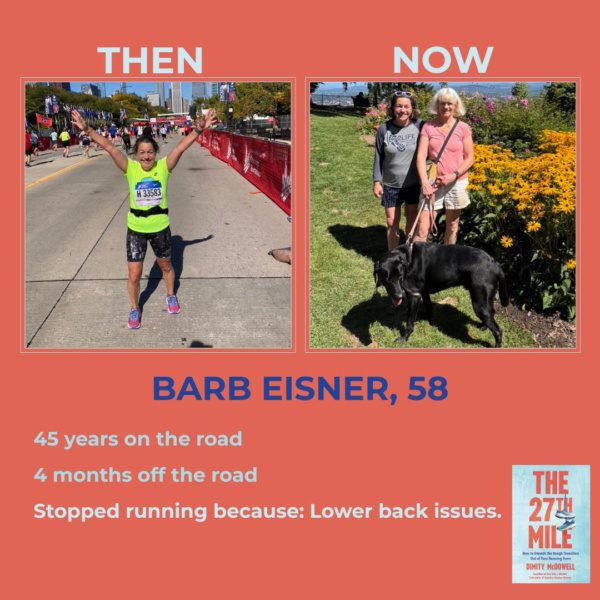

MEET SOME OF THE ATHLETES IN THE 27th MILE

Ruthie McCartney, who started running at age 40, realized her running days were over when she rode the pre-race shuttle back to her hotel; she opted not to run a half-marathon. “Who goes to a starting line but doesn’t start? I did,” she says, “I didn’t have a choice. I just knew my knee couldn’t handle 13.1 miles.” Ruthie now coaches high school track, among other things.

A severe case of sciatica took Barb Eisner down after her ninth marathon. While the pain itself was hard enough to bear, the thought of losing her running group, which she’d been part of for nearly three decades, was even more difficult. Barb continues to shows up, walking while they run. “It’s bittersweet,” she admits. “But then I remember that what matters most to me is my friendships.”

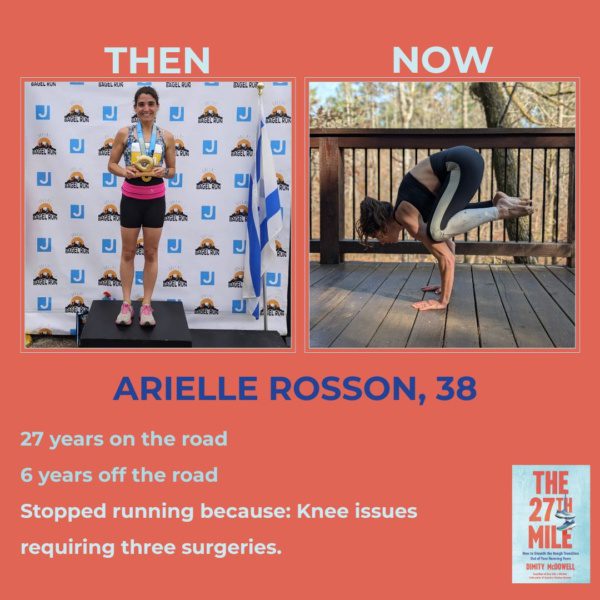

As a child, Arielle Rosson began running with her father, a marathoner. She excelled at the sport, competing at the national level. Three knee surgeries in three years forced her to stop. While yoga and other activities have (somewhat) filled the void, she continues to deeply miss her favorite sport. “I often think, ‘If only I could run again, I would never complain about anything in life ever again.’”

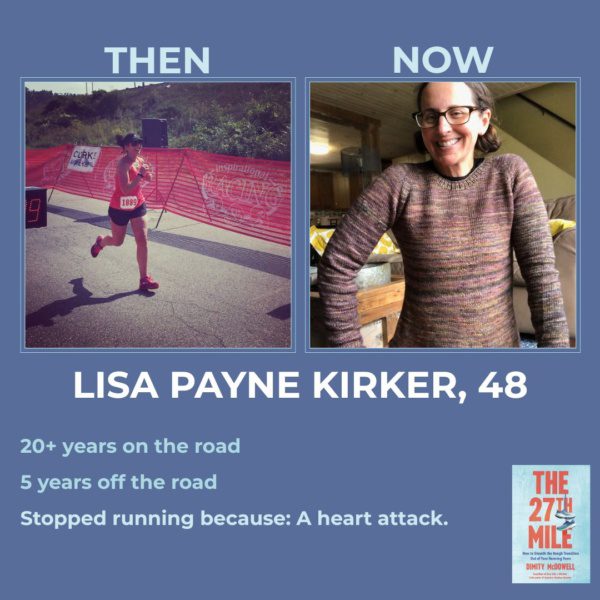

Lisa Payne Kirker suffered a heart attack at age 44. While she’s grateful for her healthy body, she also misses everything about running: the freedom, the time to herself, the pride of knocking out a marathon training run in summer heat, the sculpted legs running gave her. (“Kind of not kidding.”) Knitting, which, like running, requires hours of repetitive movement, is one of Lisa’s current passions.

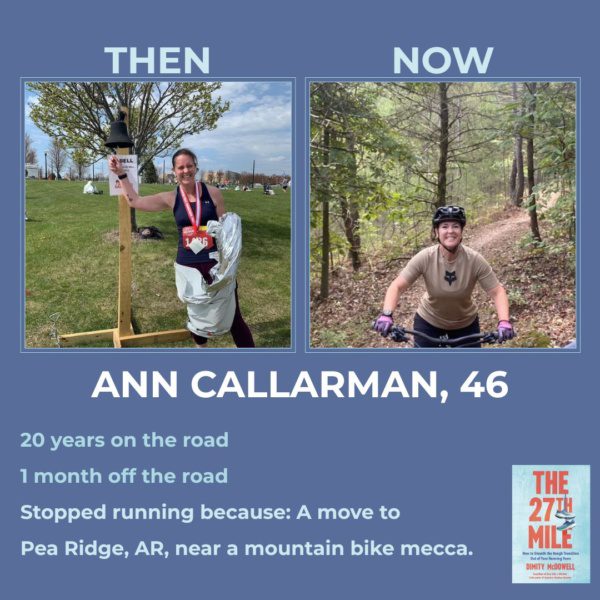

When Ann Callarman moved to Arkansas, she realized the roads weren’t great for running, but the mountain bike paths were plentiful. She bought some fat tires and was all in. Still, the comparison to the sport she did for twenty years lingers. “I’m never working as hard mountain biking as I did running,” she says, “I think that’s an incorrect statement, but it’s automatically where my mind goes.”

Stopping running gave Megan the chance to try skinning, or climbing up ski hills. She’s hooked. “I love it: my heart rate is elevated, I’m working hard, I’m sweating, I’m outside. I just feel really alive; it’s very similar to the high I used to get while running,” she says, “And it’s like running in another way: if I can’t skin for some reason, I feel disappointed and a little antsy.” Her son is now her steady skinning companion.

“I don’t know that I’m going to ever be able to run the way I used to,” Heather Escaravage explained in a therapy session, adding that running was how she identified herself and was the only way she, as a working mom, saw her friends. “Saying that out loud felt like I had just literally cleaved off a leg.” She now backpacks with her daughter, among other things.

It took Julie Baker, a runner for nearly a half century, a year for her mind to accept that her body could no longer run. “I would think, why don’t I just sign myself up for another race? I was imagining myself five years ago,” she says, “I wasn’t imagining myself realistically: potentially tripping and not feeling comfortable running.” Julie now does long hikes and walks daily with her former best running friend.