I’m not asking for sympathy, but the flow state—that feeling when hard things become easier, and your mind is so consumed with the task at hand, it doesn’t bother with worry—was much easier for me to achieve when I was running. The combination of fresh air, rhythmic footfalls, slightly labored breath, and a resonating playlist created a perfect storm for my being in the zone. Or I should say the very rare perfect storm, because not every run was nirvana. More like one in every thirty. Or maybe forty? Fifty?

All I know is that, whenever I started a run, the remote possibility existed that five miles might feel more like three. That my clomp may feel more like a float. That every cell in my body might feel ecstatic by the time I circled back to my front door.

So when I gave up running, I simultaneously gave up my flow days. I didn’t really crave them, but missed them in the way you miss a favorite sweater that had to be tossed after a moth attack. You don’t mourn the sweater, but every time you put on a similar one and realize it doesn’t quite have the feel and smell of the older one, you pause and get a little nostalgic.

Then, about six months ago, while I was walking on the Highline Canal, a female runner passed me. She was working hard, but had a smile on her face. I would have bet my post-walk Starbucks that she was deep in flow. And I can’t lie: I was envious. I wanted to be her. Sitting down later that day, I went on a little research jaunt, and came into this video from Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, a psychologist called the Father of Flow. (Side note: the video is a 2006 Ted Talk, and I love how unpolished things are: no real lighting, random chairs on the stage.)

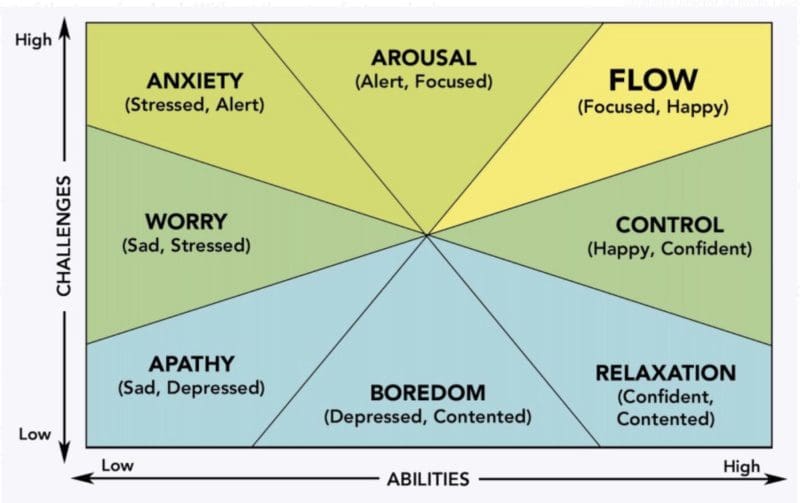

Back then, I scribbled down some notes in a random—and now probably tossed—notebook, but two stuck in my head. There are two ingredients that invite in flow: skills that are higher than average and challenges that are higher than average.

In search of that elusive top right corner, where abilities and challenges are both high.

Don’t let higher-than-average skills scare you off; although Csikszentmihalyi didn’t clarify, I took it to mean skills that are naturally learned through practice. It doesn’t mean you’re winning a marathon—or even placing in your age group. Instead, I think of that classification as skills higher than those of an average person. For instance, a runner who has run 1,000 miles over 3 years has higher-than-average running skills than somebody who has never run a step.

When I describe myself with no relation to others (see: mother, wife, sister, etc.), I often use two categories: endurance athlete and writer/content creator. I am 100% confident I’ll never climb Alpe d’Huez on two wheels, but my cycling skills are better than the average person’s. Ditto for writing: Even though my writing practice has been lackluster recently, I’ve spent most of my career in front of the screen creating content in different forms. As awkward as it feels to this Midwesterner to type this, I have some skill there too.

Instead of waiting for flow to come to me, I went looking for it. Which is a little oxymoronic, since flow can’t be forced. But what I have come to realize is that when I set up the right ingredients, then pay attention to what happens, I might just find a trickle of flow.

Three examples, since I’m a sucker for examples:

Flow Example #1: This morning, I want a challenging bike ride: I like a little pressure during my Monday morning workouts to get me revved for the week. Instead of riding by solo on Zwift (read: no accountability), I pick a group ride that, given the description, I know will require both mental concentration and physical engagement. I put on my “Get It Done, Dimity” playlist, and tell myself to just feel the pedals and not worry about the numbers.

Then, of course, I fast forward through four songs because none of them are right, and then I read a text, and, as a result, I fall to the back of the pack. Finally I power up my pedals to slide my little bike into the scrum of bikes, and hang there for about 20 miles.

Challenge? Check. Skills? Check. Flow? Check.

Flow Example #2: Last week, I sit down at the computer, close all the windows and apps except for the one I am working on. I put my phone in another room. Flow, I’ve learned, can’t come through spreading out my brain like frosting on a sheet cake. There’s just too much area to cover.

Naturally I procrastinate a bit because what if my kid is texting or I miss an important email and oh yeah, I forgot to look at We rate dogs today. But then I lean into the task [setting up the Many Happy Miles page, if you’re wondering]. The color of the images makes me smile. I relish the challenge of writing all the captions roughly the same length. I need to move around some things on the page, but I’m excited to try. I love bringing in new elements to light up a product I know well.

Challenge? Check. Skills? Check. Flow? Check.

Flow Example #3: I’m at Thanksgiving dinner. My older sister is across from me, my brother-in-law is on one side of me, and my college-aged nephew is on the other. The conversation shifts from A Wolves in Yellowstone class nephew is taking (so cool!) to how much bro-in-law enjoyed smoking turkey legs in their new pizza oven to the typical family stories that always end in laughs with my sister.

This is one of the first Thanksgivings I can remember when I felt truly calm and relaxed. Prompted by a podcast I had listened to that morning in preparation—10% Happier: Six Buddhist Strategies for Getting Along Better with Everyone—I employ one of the strategies shared, and inwardly say to myself, “This is a happy moment.”

Driving home, I realize that’s flow too. After all, families can be challenging, and I’ve had plenty of practice navigating mine.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.