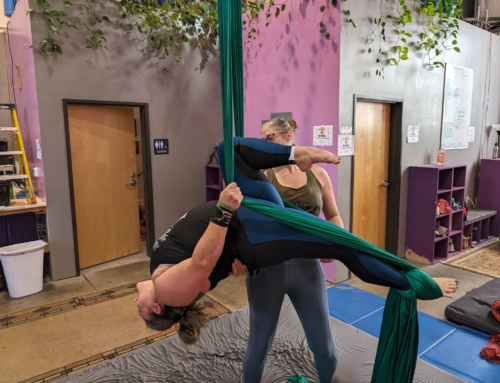

Cate, smiling and (maybe not nauseous?) after the Eugene Marathon.

[[Happily back to our Running Through It series; today, we hear from #motherrunner and writer Cate Hotchkiss and how she navigates the tricky line between running and migraines.]]

The evening before the 2017 Eugene marathon, I was reading a book in bed when suddenly, I couldn’t make out some of the words. They appeared to be blotted out by a small, dark oval with wavy lines, like a thumbprint. I blinked hard a couple of times and looked at a new paragraph, but the spot loomed, then started growing larger.

I placed the book in my lap and scanned the hotel suite. Wherever I looked—at the heavy drapes, the flat-screen TV, my race bib on the bedside table—pieces were missing, eclipsed by the big blemish, which was now shimmering. I knew I was having a migraine aura.

I got out of bed, fumbled through my purse for the hotel key card, and rushed to the bathroom where I dumped a Ziplock bag of toiletries onto the counter. I popped two ibuprofen and, with my empty bag, headed down the hallway in my pajamas to the ice machine. I packed the bag with ice. The shimmery oval morphed into a jagged, metallic starburst, like a speech bubble in a comic strip—one that says, Kapow!

I hurried back to the room, crawled into bed, placed the bag of ice on my forehead, and braced for the hard kick of the migraine: some degree of headache, nausea, dizziness, and fatigue that would last from a few hours to a couple of days. Even though I’ve suffered from migraines for more than two decades, I never knew what I’d get.

But first, and for the next 20 minutes before the aura burned out, I’d watch a stream of brilliant starbursts light up the dark.

***

If you get migraines, you know that they’re not just severe headaches. Migraine is a genetic, neurological disorder with a host of symptoms that can affect your entire body. A recent study shows that worldwide, it’s the third most disabling disease in people under 50. And, among all ages, it ranks in the top 10.

Migraines afflict 36 million people in the U.S., and one in five women, according to the American Migraine Foundation. Furthermore, women are three times more likely to suffer them than men. Approximately 30 percent of people with migraines experience auras, or temporary disturbances in visual, sensory, motor, or verbal functioning.

Cate’s dog, Harper, and daughter, Amelia: a great pic amidst migraine yuck.

My migraines started in my early 20s, but fortunately, for most of my life, they weren’t chronic. I’d get four or five a year—disruptive and painful, but manageable. However, in my mid-40s, likely due to hormonal changes, they hit weekly and now included (bonus!) disabling vertigo. It took months of trial and error to find the right cocktail of meds and other therapies to mitigate the attacks and symptoms.

And yet, sporadically they still strike—like the one did the night before the Eugene marathon.

***

When the alarm sounded at 4 a.m., the worst of the head pain had subsided, and I wasn’t dizzy—a big win. However, the nausea was intense and I was skeptical I could run through it, especially at a pace that would qualify me for Boston.

Nonetheless, I got up, brewed a small pot of coffee, and heated up a bowl of oatmeal. I wanted to call my husband, my sounding board, for support, but he’d still be sleeping. He usually joined me at races, but our two kids had too much going on that weekend for both of us to be out of town.

Cate and her other child, John in the great outdoors.

Instead, I turned to writing, as I often do, to help sort out my racing thoughts. I opened my laptop and journal file. At the top of the page, I’d pasted a quote by one of my running heroes, Olympian Kara Goucher, which reads: “There are a million reasons why you can’t. Focus on the few reasons why you can.” I decided to write a short list of why I can:

- I’ve trained hard and, at times, through migraine symptoms, too.

- I’ve run six marathons. My body knows how to do this.

- If I throw up on the course, I certainly won’t be the only one.

But when I started to write how I’d feel if I didn’t run, I stopped. My body tensed up. If a migraine equaled no race, what would it take from me next? I flashed back to those 18 months when simply getting out of bed each morning was a torment; when I felt as if I were failing in every role—as a mother, wife, friend, writer, runner—and when I wondered if I’d ever feel good again. I didn’t want to go back there.

I closed my laptop. I pinned on my bib. And, at 5:45 a.m., I boarded the shuttle bus to the race.

An hour later, I was shivering in front of Hayward Field in corral C with all the other nervous runners wearing shorts in 39 degrees. When the gun fired, we moved together as a pack before fanning out and finding our own paces. Mine was slower than what I’d trained for, and from the initial strides, I felt like hell.

I was hoping, though, that after the first few miles, things would improve. They didn’t. The nausea was unrelenting, and my body heavy, as if it were being pressed into the pavement.

Another great Cate pic; guessing her head is feeling clear + free in the mountain air.

I took several deep breaths and tried to smile, as if to trick my body into thinking it felt good, a strategy I learned from my dear friend, Alicia, who ran the NYC marathon with a stress-fractured foot. By the 10-mile mark, the nausea had abated enough to pick up the pace, and aside from my sludgy legs, I felt okay. Maybe, I thought, I could still meet my B goal of finishing in under four hours.

Unfortunately, while cruising on the shaded bike path alongside the Willamette River, I hit the wall hard at mile 20, which triggered a tidal wave of nausea. At the next aid station, I took off my hat and dumped a cup of water on my head. But the heat wasn’t the problem, and the water only streaked my sunglasses and streamed salt into my eyes.

At that point, I just wanted to walk, or better yet, sit under a giant shade tree.

But then a runner who appeared to be at least a decade older came zooming by me. I thought, damn, if she can do it, and which inspired me to keep scuffling from aid station to aid station until I managed to pick up my feet for the last half mile and kick through the final stretch into Hayward Field.

I crossed the finish line in 4 hours and 6 minutes, neither meeting my A nor B goal, but that hardly mattered. What did matter: I now had a bib whose numbers were obscured only by a solid, shimmery medal.

Wow what a great story. I am sorry that you had to run a marathon feeling so horrible but you should be so proud of yourself for finishing and accomplishing this despite not feeling your best. While you didn’t meet your A or B goal, you finished in a more than respectable time. Heck, finishing at all, given your condition at the time, would have been more than enough. Good job!

Thanks for sharing this! I am a migraine sufferer, too, and it can be so debilitating. Great job “running through it”!

So inspiring! Way to go, Cate! :)

Have had intermittent migraines in the past, but none for a couple years. This sounds horrible. Amazing work getting this race (and, no doubt, so many other challenges in life) done!

Thank you for your kind words, BAMRs. I am grateful for this supportive tribe.

An inspiring story told well. You have much going for you despite those damn headaches. Keep up the good work. Love Charlotte and Henry

Great story of perseverance. I have a traumatic brain injury, idiopathic intacranial hypertension and pcos all causing sometimes daily migraines. I’ve tried most all the treatments. I’ve learned to live with them. But I don’t walk outside or drive because of my conditions. I had weight loss surgery in April and have lost 60 lbs. I want to start running and I came here looking for inspiration and have found that. Thank you, God Bless.