Earlier this fall, I was delightfully entertained while reading some hilarious comments in an online running group. One runner was getting married, and she was looking for ways to cover up the very obvious tan line from her fitness watch. The best response was, “Just wear your watch during your wedding. How else are you going to track those steps down the aisle?”

The Pew Research Center conducted a survey in 2019 and found one in five people wear some kind of tracker. My own Garmin Vivoactive lives on my wrist as permanently as the freckles on my arm. I can’t deny my committed relationship with my watch since it tracks everything from my period to my mileage.

Watches, essentially, are tools that collect data. And the more you wear yours, the more data you’re collecting about yourself. But sometimes I wonder if GPS accuracy is as on point as I hope it would be.

To get a better understanding of what our watches can do—and to see if their data might be overly optimistic—I reached out to a few experts.

Would my bar graphs of deep sleep or VO2 max rating hold water under their scrutiny? Are my mile repeats really a mile?

“These are common questions.” says William Byrnes, a professor of Integrative Physiology at the University of Colorado Boulder. “Monitoring parameters like calories burned and sleep patterns have important implications for optimizing health and athletic performance, but the monitoring devices need to be accurate.”

DISTANCE: PRETTY DANG GOOD

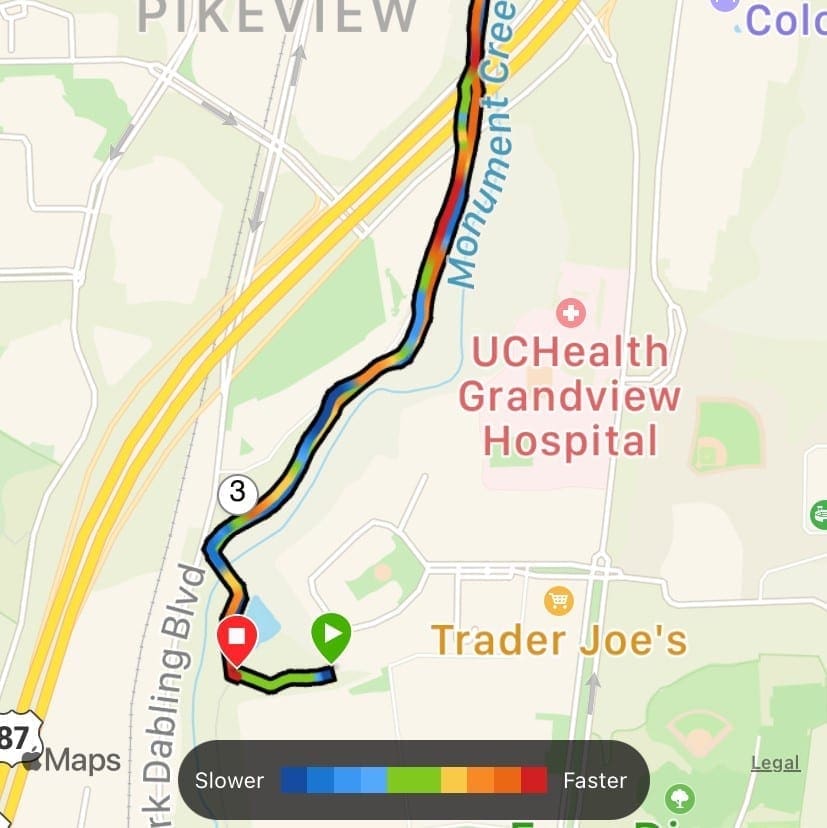

The GPS feature our devices use is just a series of tracking points. The GPS “checks in” every few feet, notes where you are, and records how quickly you’re getting there. Each check-in is a tracking point. Add up all the tracking points and you have your total distance. Different watches and apps have various algorithms to calculating distance, which is why Strava might say you ran 3.63 miles while your watch says 3.52. Most times the differences are minimal.

“I’ve had a Garmin since about 2005 and am happy to see how much better the distance and pacing features have become. These just keep getting better,” says Dr. Andrew Subudhi, Professor of Human Physiology and Nutrition at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs.

“GPS devices can accurately measure speed and distance when exercise is performed outdoors, but this does not help with exercise on indoor devices like treadmills, steppers, and stationary bicycles,” adds Byrnes. Indeed. When you finish a treadmill run and the image on Strava looks like a 2-year-old went nuts with a red crayon, that’s why.

HEART RATE: DECENT IN CERTAIN SITUATIONS

One of the greatest changes we’ve seen in recent years is the transition from heart rate measured solely with a chest strap to heart rate measured through sensors on a wrist device. Watches and arm straps use photoplethysmography (PPG), which is the fancy word that describes the process of using light to measure blood flow. It’s pretty amazing to see those little flashing lights on the back of my Garmin and know they’re calculating the way my blood is moving through my veins. But does PPG work?

“Heart rates measured from light sensors on the wrist can be pretty good at rest, but often become questionable during exercise, when movement distorts the measurements,” Dr. Subudhi says. This is evident in one 2017 study from The American College of Sports Medicine that showed great results with PPG heart rate monitors on a stationary bike and a treadmill, but performed poorly on an elliptical trainer with arm levers. Depending on the device, the study showed error margins of up to 25%. It’s not to say your heart rate data is completely unreliable, but the gold standard for measuring heart rate will always be a chest strap.

Also, remember that our heart rates are finicky. They’re unique and they can be affected by any number of things. “Heart rates can be influenced by emotion, as well as thermal and altitude stresses,” Byrnes cautions. Keep that in mind the next time you’ve argued with your four-year-old for the 100th time about the importance of wearing a coat and wonder why your afternoon run showed a higher heart rate.

SLEEP DATA: PROBABLY NOT SUPER ACCURATE

I asked Byrnes about the sleep data on my Garmin. His response was cautious. “Regarding sleep, there seems to be a disconnect between the devices and what is actually happening.” This bore out in a study on the validity of activity monitors in The Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport from 2015. The participants in the study were elite cyclists, and researchers noted when the athletes trained at high levels, their bodies had a tendency to move more during sleep, naturally looking for ways to get comfortable or stretch those sore muscles. But that turned out to be a problem. It looked like more movement correlated to more awake time on each device, whether that was true or not.

Our watches look at how much we’re moving at night; measuring that way tends to underestimate sleep duration and overestimate wake duration. So if you thrash around in your sleep or you’re in the midst of a training cycle, you’re probably not getting the most accurate results.

VO2 MAX, STRESS LEVELS + OTHER DATA POINTS: ROOM FOR IMPROVEMENT

What about all those other watch features, like VO2 max and stress levels? “Biological signals are also getting better, but aren’t quite as precise as I wish they were,” Dr. Subudhi notes. “The information these watches display are not actually measured, but predicted [with] the information gathered from the GPS and light sensors. Typically, the prediction equations manufacturers use have been developed and validated on large groups of people, but aren’t truly specific to the individual wearing the watch.”

“VO2 can be predicted from heart rate and pace, but there can be a lot of error,” he adds, “I’m a scientist, so I generally don’t trust numbers that aren’t actually measured.”

Dr. Subudhi and I are not here to break your heart about your stellar fitness age or brag-worthy REM sleep cycles. Not everything about your watch and what it’s reporting needs to be thrown out the window. Instead, think of this as just a friendly reminder that what your watch tells you—and how your body feels—can be two separate things, and evaluating them both as during a workout (or a restless night) will bring you the most balanced perspective.

I’m glad to know why I get so little “deep” sleep! This is all very interesting and a good reminder to remember to think about how we actually “feel” rather than what a watch tells us. My GPS can be finicky for various reasons and flatter me with lies like giving me an “award” for running my Fastest! Mile! Ever! — of a 7:27 pace, which is just laughably untrue (I *may* have run under 10:00, but don’t bank on it).

Related: My daughter’s Apple Watch measures distances that are wildly inaccurate, telling her she ran 3 miles when it’s more like 2.5. I know we can re-set it somehow, but we haven’t had enough desire or energy to deal with that.

Thank you for all this detail!

I have seen so may discrepancies between my Garmin, my iPhone Health tracker and the actual miles calculated in a race. When I run in a race, especially a half marathon, I will always prepare for at least a .10 mile longer on my watch than the actual markers on the route. Sometimes, I find it disappointing when I see the miles on my watch compared to my iPhone. To keep it consistent in my mind, I will always use my good ‘ole Garmin for tracking distance and time. it does track calories burned too but that’s another whole discussion. Thanks for sharing.

I was wondering if anyone else had experience with their Garmin while running in hilly areas. When I run in more mountainous areas my VO2 max and fitness level decreases. I feel like it doesn’t know I’m running up steep hills, and that’s why my pace is lower, not because I’ve just started running slower with an increased heart rate. Can anyone shed any light?

I found a .25 mile difference between my FitBit and my phone with tracking distance. The pace difference was over a minute! I had some suspicions when I felt like I was hitting a good pace and my Fitbit was like “no you’re not.” Now I use both and kinda average them out.

I love my Garmin Venu. I know not all data is correct but it gives me a starting point and in return a goal. I will admit I do get competitive with it/myself – Not always a good thing. My fitness age is half my actual age. I’ll accept that any day running and walking mileage outside is very accurate. The stairs climbed function is almost always inaccurate, frequently telling me I descend far more then I climb.

My Garmin says I have a fitness age of 20 too! I’m a lot closer to my 50th birthday so I’ll happily take that stat. But when the temps outside have been 4 degrees (C) or lower I’ll get these crazy heart rate readings of 200 when I’m pretty sure I wasn’t breaking 165. I think I’d have known. I’d probably have been laying in the street gasping for breath. The distance readings are pretty accurate but most other things I take with a grain of salt.

I have a Garmin 345 and it routinely says I sleep over ten hours a night even though I have a five year old who has bad dreams and a husband who snores! I rarely pay attention to that feature. The HR can be erratic when not running…if I am doing HIIT at home, it will say I am at a warm up HR and I can barely catch my breath. I guess I have just learned to gauge things more on what my body feels like that what my watch says! I will say that it tracks distance extremely well and it is only ever off maybe a .10/mile.

Very interesting post. Thank you. It drives me nuts when people measure their progress with the VO@Max the Garmin provides. This means they have no clue what VO2Max is.

DC Rainmaker publishes INSANELY detailed information about the accuracy of the GPS function on various watches for anyone who is curious. He has reviewed basically every smartwatch. Here is his info on the Garmin Venu for instance: https://www.dcrainmaker.com/2019/09/garmin-venu-with-amoled-display-everything-you-ever-wanted-to-know.html

I never rely on the sleep function of either my Garmin Forerunner or my Fitbit Versa 2; there’s a LOT of room here for improvement. A voracious reader, I NEVER go to sleep before reading at least an hour in bed, yet my watch will consistently report that I went to sleep the moment I climbed into bed with my Kindle. And, I’ve always been a very kinetic sleeper — my sisters refused to share a hotel bed on vacations growing up, so I always got my own! — but that will show as my having awoken repeatedly when in fact I rarely awaken during the night.

The real question is, does anyone have a Fitness Age that’s not 20?? That’s the only one I’ve ever seen among my friends! :) I do have to laugh about the race predictors. I feel like I’m really letting my Garmin down because I’ll never come close to those predictions. Crazy fast!