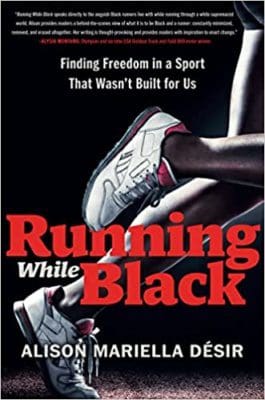

We’re honored to share an excerpt from Alison Désir’s new book, Running While Black. Désir shares how she came to love running because of the structure and health benefits (mental + physical) it brought to her life. But as she dug deeper into the history of running, it became increasingly clear the fitness industry as a whole has rarely been inclusive to people of color. Désir writes the story of how she blossomed as a runner while challenging the status quo in a sport that has all too often been a place of privilege.

Be sure to tune in to the AMR Podcast when Sarah interviews Alison Désir to discuss the book in detail.

After the 2016 election, I found myself thinking a lot about the future of our country and about the ways in which the forces of racism and sexism play out on both a national scale and a personal one. Since founding Harlem Run, the sexism I’d experienced in the running community had been painful and disheartening.

In many ways, the man entering the White House operated in the same manner—name-calling those who didn’t agree with him or follow in line with his bidding, stoking division to gain power. It was terrifying to imagine that this person would set the agenda for our nation for the immediate future. His mindset was “win at all costs” and he pushed a nationalist (read: white, cisgendered, able-bodied, Christian male) agenda. I was frightened for my people. His laws and policies would further marginalize those already marginalized, Including Black people, the LGBTIQ+ community, undocumented people, Indigenous people, and women. The incoming administration was already discussing rolling back reproductive rights. Any cuts in funding and changes to reproductive rights would disproportionately affect women of color. Where rights and access are concerned, we’re the first to be negatively impacted and the last to be considered. Our agency over our bodies was on the line.

All of this was on my mind in December 2016, when Amir and I had a long conversation with a friend of his who worked at the White House during the Obama administration, and his partner, who we’d gotten to know. I told them about my work with Harlem Run, how it was a political act in the sense of claiming space, advocating for our community, and centering the experiences of Black people and other people of color. Amir’s friend was enthusiastic, as he believed communities like Harlem Run were deeply important in the larger political theater. He also emphasized how damaging the new administration’s policies would be, particularly to people in neighborhoods like Harlem. “You have a powerful voice and powerful community,” he said. “You could really do something impactful, using movement.”

My mind jumped to the history of movement as protest, to Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil rights marches. More than 200,000 demonstrators rallied together in the March on Washington in 1963 to demand equality. In 1965, thousands joined the fifty-four mile walk from Selma to Montgomery over a five-day period, with 25,000 people walking the final leg to the Alabama State Capitol. These collective actions reminded me of the power we have when we speak with one voice to demand the rights we deserve. How could I use running in the same way?

Our friend brought up the Women’s March planned for January 21, 2017, the day after the inauguration, which was shaping up to be one of the largest marches of our time. His partner added, “You could run there?”

Amir and I looked at each other. My mind was already racing, thinking about the way the endeavor would bring together all these threads—movement, protest, running, and community. After turning it over for a couple of hours, I asked Amir what he thought about me running solo from Harlem to Washington, DC—not just to do it, but as a fundraiser for Planned Parenthood, timed to arrive the morning of the Women’s March. “Oh, yeah,” he said in his understated way, implying this was a foregone conclusion. “I’ll drive alongside you.”

I pulled out my phone and calculated the distance—250 miles. Would it be possible for me to complete the mileage by myself?

Everything accelerated after that. We decided we’d add three more runners to make the distance manageable, and I created a GoFundMe page—(Four Women) Run For ALL Women—trusting that the logistics would work out. Planned Parenthood’s CEO tweeted about our effort, and the organizers of the Women’s March said they were pumped for our participation. More than one hundred women reached out wanting to take part in the run. Like me, they were worried about the rollback of reproductive rights, particularly because we’d learned the new administration would likely withhold federal funding from Planned Parenthood, making our effort more urgent both in dollars and in principle. My friend Mary, who gave me the Harlem Run domain, jumped on logistics and created a spreadsheet that broke down the run into four-mile segments, with times and locations so people could sign up to join us.

Eight days into our fundraising, we went viral. We broke my initial fundraising goal of $44,000 (in honor of Barack Obama, our forty-fourth president), with donations coming in from people around the world. Our sign-up sheet was so full we told people not to worry about signing up and to just show up! They could follow us on Twitter and Instagram for location updates. I started fielding calls from news outlets in Canada, Ireland, and Australia. Stories ran online on Glamour, the Cut, Bustle, Essence, and more, all linking to the GoFundMe page, all discussing the threat to women and our desire to raise awareness and money for Planned Parenthood.

What we were doing, then, was an act of reclamation, a reclaiming of body and voice for Black women, then and now. All women would be harmed by the new president’s attacks on women, and that meant Black women and women of color in particular. We’re more likely to rely on Planned Parenthood’s services, in part because more Black women live in poverty than white women. If wealthy white women need an abortion, they have options. Many Black women don’t. When women cannot access healthcare—from basic checkups to birth control to an abortion—or make decisions for themselves, terrible consequences follow. Education opportunities can be lost, affecting future employment. A woman’s health, the health of her family, and therefore the health of her community all suffer. Our bodies, running through the night, were a declaration that we will not be silenced or controlled. We will run and we will fight.

From RUNNING WHILE BLACK: Finding Freedom in a Sport That Wasn’t Built for Us by Alison Mariella Désir with permission from Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2022.

Thank you, AMD! Run For All Women! VOTE For All Women!

This is such an inspiring story and mission! Thank you for being a strong leader advocating for communities that are often ignored or discounted.